Reviews of More Sawn-Off Tales

Litro magazine October 2013

More Sawn-Off Tales is the follow up to 2006’s Sawn-Off Tales, but don’t be deceived by its title- there’s nothing haphazard or carelessly truncated about this acerbic and darkly humorous collection of short stories.

With a poet’s eye and an iconoclastic sense of humour, David Gaffney conjures a technologically addled and socially inept world comprised of 69 pieces of flash fiction. There’s a frenetic and imaginative cast of characters contained within: smell comedians, blood spatter analysts, bad and burglarising psychiatrists, feral lambs and alpacas all make an appearance. Each piece is 150 words long, and with punchy openers such as “I helped Ivan load the eyes into his van” or “My penis grew so huge I became house-bound”, Gaffney proves himself to be a master of the surreal, arresting and story-rich first line.

Isolation, in all of its myriad incarnations, as well as the drudgery and inertia of middle-class existence, form the main themes of this collection. These entertaining vignettes are shot through with pathos and a subversive streak of knowing social commentary: this is micro fiction that is aimed for, and also aimed at gently lampooning, a particular kind of smart phone-glued, self-consciously cultured and affected Generation Y set.

Sight & Sound magazine, Sadler’s Wells theatre, Boards of Canada, Detroit techno and “folktronica” artists get name checked- but thankfully these hipster references are passing and humorous and thus do not veer into the realm of elitism or gratuitousness. A deliberate and playful sense of satirical pretension is clearly shown in pieces such as “The Bear’s Head”, where a stuffed bear’s head gets rejected from being placed on a pub wall:

“’It looks left-wing,” the landlord said.

‘’A trendy bear that belongs in a wholefood café, not a pub.’”

In “The Periphery is Everywhere”, a couple engages in a pseudo-intellectual discussion. The conceptual jargon they level at each other serves to inadvertently reveal their inability to actually communicate or fully articulate their estrangement:

“I said her resentment of me was so big I could get inside and walk around.

She said, yes, emotions can have spatial characteristics.

I said experience is an ambulation that concatenates multiple overlapping relations.

She said I was like a cat watching contemporary dance.

I said the felt reality of experience is interwoven at the fringes of perception with the conjunctively structured envelope of waveforms.

She couldn’t think of anything to say to that.”

The humour is sharp and pointed, occasionally a wince or knife-edge away from seriousness. There’s not a word out of place- Gaffney is a writer in full control of his material and there is a wry consistency to the voice and tone of these curious, casually fantastical pieces. Stories veer from quiet hilarity and arch satire into the realm of the macabre, nightmarish and baffling. GoreMen and women struggle to make emotional connections in a series of unusual ways: through living in art installations, dissecting the mechanics of romantic meals, selecting the same paint colour, “Bleached Lichen Number Four”, for their walls, or vegetating outside of the city for the holidays- all to no avail, for “even out here, even in the countryside, they were no closer.”

Gaffney has a gift for unpeeling banality to reveal the absurd and quietly disappointing in the everyday, as this passage from “The Zoo With Three Animals” demonstrates:

“My mother told me about the zoo with three animals. It was called Preston Pleasure Gardens and there was a baboon, a monkey and an ostrich. I thought it was a shame that the baboon and monkey were the same type of animal as it made it appear that the zoo had only two animals. But really it had three.”

Gaffney has been described as “David Shrigley meets Curb Your Enthusiasm” and he does share some similarities with Shrigley in terms of uncovering black humour and absurdity in the everyday. There are also comic shades of Chris Morris and Armando Iannucci. However, Gaffney has a wit and aesthetic that is uniquely his own- the collection is undoubtedly weird, and seems to dwell upon an ocular fixation. Vans and rivers full of eyes are a recurrent motif; perhaps a commentary on an increasingly surveillant society. “The Scientific Explanation for Faraway Eyes” is also explored. The collection tends to read a little repetitively toward the end, but standout pieces such as “The Three Rooms in Valerie’s Head”, “Nothing Can Hurt Me Now” and “It Doesn’t Really Matter If Things Die Out” are terse and funny meditations on love, loneliness and death which invite rereading. Through artful depictions of crumbling or static relationships amidst surreal contexts, Gaffney weaves the everyday and the bizarre with finesse and aplomb.

More Sawn-Off Tales is the follow up to 2006’s Sawn-Off Tales, but don’t be deceived by its title- there’s nothing haphazard or carelessly truncated about this acerbic and darkly humorous collection of short stories.

With a poet’s eye and an iconoclastic sense of humour, David Gaffney conjures a technologically addled and socially inept world comprised of 69 pieces of flash fiction. There’s a frenetic and imaginative cast of characters contained within: smell comedians, blood spatter analysts, bad and burglarising psychiatrists, feral lambs and alpacas all make an appearance. Each piece is 150 words long, and with punchy openers such as “I helped Ivan load the eyes into his van” or “My penis grew so huge I became house-bound”, Gaffney proves himself to be a master of the surreal, arresting and story-rich first line.

Isolation, in all of its myriad incarnations, as well as the drudgery and inertia of middle-class existence, form the main themes of this collection. These entertaining vignettes are shot through with pathos and a subversive streak of knowing social commentary: this is micro fiction that is aimed for, and also aimed at gently lampooning, a particular kind of smart phone-glued, self-consciously cultured and affected Generation Y set.

Sight & Sound magazine, Sadler’s Wells theatre, Boards of Canada, Detroit techno and “folktronica” artists get name checked- but thankfully these hipster references are passing and humorous and thus do not veer into the realm of elitism or gratuitousness. A deliberate and playful sense of satirical pretension is clearly shown in pieces such as “The Bear’s Head”, where a stuffed bear’s head gets rejected from being placed on a pub wall:

“’It looks left-wing,” the landlord said.

‘’A trendy bear that belongs in a wholefood café, not a pub.’”

In “The Periphery is Everywhere”, a couple engages in a pseudo-intellectual discussion. The conceptual jargon they level at each other serves to inadvertently reveal their inability to actually communicate or fully articulate their estrangement:

“I said her resentment of me was so big I could get inside and walk around.

She said, yes, emotions can have spatial characteristics.

I said experience is an ambulation that concatenates multiple overlapping relations.

She said I was like a cat watching contemporary dance.

I said the felt reality of experience is interwoven at the fringes of perception with the conjunctively structured envelope of waveforms.

She couldn’t think of anything to say to that.”

The humour is sharp and pointed, occasionally a wince or knife-edge away from seriousness. There’s not a word out of place- Gaffney is a writer in full control of his material and there is a wry consistency to the voice and tone of these curious, casually fantastical pieces. Stories veer from quiet hilarity and arch satire into the realm of the macabre, nightmarish and baffling. GoreMen and women struggle to make emotional connections in a series of unusual ways: through living in art installations, dissecting the mechanics of romantic meals, selecting the same paint colour, “Bleached Lichen Number Four”, for their walls, or vegetating outside of the city for the holidays- all to no avail, for “even out here, even in the countryside, they were no closer.”

Gaffney has a gift for unpeeling banality to reveal the absurd and quietly disappointing in the everyday, as this passage from “The Zoo With Three Animals” demonstrates:

“My mother told me about the zoo with three animals. It was called Preston Pleasure Gardens and there was a baboon, a monkey and an ostrich. I thought it was a shame that the baboon and monkey were the same type of animal as it made it appear that the zoo had only two animals. But really it had three.”

Gaffney has been described as “David Shrigley meets Curb Your Enthusiasm” and he does share some similarities with Shrigley in terms of uncovering black humour and absurdity in the everyday. There are also comic shades of Chris Morris and Armando Iannucci. However, Gaffney has a wit and aesthetic that is uniquely his own- the collection is undoubtedly weird, and seems to dwell upon an ocular fixation. Vans and rivers full of eyes are a recurrent motif; perhaps a commentary on an increasingly surveillant society. “The Scientific Explanation for Faraway Eyes” is also explored. The collection tends to read a little repetitively toward the end, but standout pieces such as “The Three Rooms in Valerie’s Head”, “Nothing Can Hurt Me Now” and “It Doesn’t Really Matter If Things Die Out” are terse and funny meditations on love, loneliness and death which invite rereading. Through artful depictions of crumbling or static relationships amidst surreal contexts, Gaffney weaves the everyday and the bizarre with finesse and aplomb.

The Big Issue

In More Sawn-Off Tales Gaffney demonstrates his mastery over flash fiction, as he evokes sadness and humour in equal measure through the often tragic but fully formed characters in 70-plus stories.

The Big Issue May 2013

Short, Sharp Bursts of Weird

Give David Gaffney 150 words and you’ll be holding his hand as he leads you to some very strange places. More Sawn-off Tales is the second in the writer’s Sawn-off flash fiction series and this collection comprises 73 disquieting stories, each exactly the same in length. Whether describing using crossbows to hunt sheep, or the sound of bass-heavy techno killing an alpaca, Gaffney’s prose carves out a place in the weird corner of the room and doodles contentedly all over it for the afternoon. His miniature stories, creepy and amusing in equal measure, are a glimpse into a hive of the uncanny.

It must be said of the author that through his collections with Salt he has managed to bring the appealing medium of the tiny story to a much wider audience. Nestling snugly between poetry and conventional short stories, flash fiction deserves the ‘iPad generation’ moniker it has attained. There seems something intrinsically modern about the form (its National Day came, after all, only in 2012) and Gaffney can claim to be one of its most skilled practitioners. In a period in which, to a greater extent than ever before, fiction vies for attention with many multifarious forms of entertainment, flash fiction could well be one of modern literature’s real success stories. ‘No one had a job because everybody made their own things with 3D printers’, Gaffney writes of the future in ‘It Doesn’t Really Matter if Things Die Out’. It is only a mild exaggeration.

First, though, a reservation. In part because they are so short, the stories fall victim at times to various ailments. ‘A Dress Code for Modern Musicians’, for example, feels like a list rather than a narrative; ‘It’s All in Storage’ seems set on a stage only a much longer story can fill; and ‘Let’s See What Rachel’s Been Up To’ is simply too heaving with bizarre references to care much about. It would be intriguing – and, more than that, sometimes necessary – to hear more about the inhabitants of some of Gaffney’s stories, and for this reason the confines of the format serve occasionally to restrict rather than purify the writing. Not the worst criticism for a writer to receive but a reservation nonetheless.

There is so much to enjoy in the writing, however, that the duds don’t leave much of a stain. It is an absolute pleasure to read some of the imagery and allusions with which Gaffney peppers his work and he frequently exhibits a turn of phrase that is simply enchanting. We are treated to lines like ‘You are so bold with cobalt, Terence’ and ‘Izzy removed her clothes and crept towards me like a foal tiptoeing through the snow’. Gaffney knows how to paint a powerful picture and does so time and time again: ‘suddenly my anus became a gaping, gelatinous mouth and the tube wormed up inside me like a long, thin girl swimming up a pipe’ is a sentence Carol Ann Duffy mightn’t be brave enough to set down in print.

Several stories stand tall above the rest as particularly effective syntheses of the comical and the bizarre, or the strange and the profound. ‘The Joke About Todd Pokato’, for example, is sublimely funny; and ‘The Building with the Hole’ offers one of the collection’s most touching lines: ‘she said sunshine was like a friend: at its best on first meetings and farewells’. Shades of Luke Kennard loom into view in some of the pieces – as, for example, in ‘Listed Bridge’ (‘I was able to climax only with the aid of a physical theatre company’) and ‘Happy Birthday, Hee Hee’:

‘It’s not Jim’s birthday,’ Martha explained. ‘It’s just something we say around here.’

‘So what do you say,’ I asked, ‘when it really is someone’s birthday?’

‘We don’t say anything.’

Central to many of the pieces is the concept of borrowing or inhabiting others’ bodies and possessions (‘The Homes of Others’; ‘It Happens Inside’) and breaking up with partners or making fresh starts (‘Bleached Linen Number Four’; ‘Blood in Fight’). More often than not, characters in More Sawn-off Tales are unsatisfied with the hand they have been dealt and are looking for ways to shuffle the deck.

The afore-mentioned Izzy appears twice in the collection, on both occasions able only to have sex under certain strange conditions. Indeed the tales show evidence of a writer preoccupied with not just the bizarre but the sexually perverse: we are witness to fetishists having sex with eyes; a member of a theatre troupe being plastered to a wall with semen; and a couple booking a viewing of a property simply to have sex in it. Is Gaffney visualising a world in which these fixations are commonplace, or hinting that they lurk at the bottom of this one, unacknowledged and suppressed?

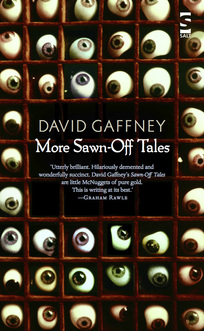

Eyes are a subject to which Gaffney returns with macabre relish; a search for the word indicates that it is included 28 times, and indeed 42 of them adorn the front cover of the book. In one story he discusses their transportation, and in another contemplates the logistics of implanting those of an ex-girlfriend into those of a current one. The ‘thorough and professional’ eye of his proofreader is credited at the beginning of the collection but this rubs salt in the wound when it becomes apparent that at least three errors seem to have escaped her grasp: the misspelling of ‘alpaca’ in the title of ‘DJ Stinger and the Ghost Alpcaca’; a character in ‘Blood in Fight’ being called first Maria, then Marie, then Maria again; and inconsistent title formatting. Small oversights, perhaps, but noticeable ones in stories of such brevity.

‘A Dress Code for Modern Musicians’ causes the book to limp out slightly but it has walked so tall thus far that it matters little. By the time one has finished reading Gaffney’s collection one is living deep in the midst of his strange creation, wondering why not everyone in the real world behaves in the same fiendishly weird manner. It’s not that they shouldn’t do so; it’s just that if they did, Gaffney wouldn’t have released More Sawn-off Tales. To escape into his imagination is an experience no amount of 3D printing can replicate.

Ralph Jones, August 2013, for Sabotage Magazine

Tusk Magazine

This is a delicious collection of short stories, very short stories, with each one exactly 150 words long. They are the prose equivalent of the Haiku, the Japanese poetic form that consists of just three lines. Like the Haiku, many of David Gaffney’s stories are opaque, enigmatic and surreal, the meaning tantalisingly close, but just out of reach.

His publishers characterize David as an “expert miniaturist with the ability to stuff an elephant inside a flea without the insect noticing.” Even the PR blurb is surreal. It’s been ‘Gaffnified.’

His characters are usually on the fringes, fragmented, looking to connect. Gaffney himself comes from Cleator Moor in Cumbria, a dismal town in the west of the county and he gives the town credit, if credit is due, for influencing his writing. “Many of the characters I write about are on the edge of life and maybe that’s related to Cleator Moor. It’s like a scruffy loner looking in, perhaps feeling left out a bit and badly used.”

The titles of the stories reinforce that sense of alienation – Everything’s West of Something; It Doesn’t Really Matter If Things Die Out; It’s All in Storage. The characters of More Sawn Off Tales are the antithesis of the socially networked, and linked in. They are the dis-connected and left out. Yet there is more to these tales than just social exclusion. The Clever People Who Can’t Do Anything Useful is a witty, shrewd and bitchy piece on a type we’ve all come across, the person who has never found a challenge to match their talents. Their genius remains dormant, undiscovered and they are only too happy to tell anyone who will listen just how undiscovered they are. And where do they live? According to Gaffney, they live in Hebden Bridge, a line that gave me a wonderful sense of recognition. I’ve known many such types who hail from this gentrified Yorkshire mill town.

The List

In More Sawn-Off Tales Gaffney demonstrates his mastery over flash fiction, as he evokes sadness and humour in equal measure through the often tragic but fully formed characters in 70-plus stories.

The List May 2013

When reading this collection of very short stories you will forget where you are, what you’re supposed to be doing and where you’re supposed to be going. It is utterly, and wonderfully addictive. Each 150-word story in this follow up to Sawn Off Tales is a self-contained universe, each a world where reality becomes irrelevant, and it’s the words that matter.

The strongest stories are the ones that explore detached and dysfunctional characters. For example, in It Happens Inside a radiologist X-rays items she has stolen from her neighbour in order to get to know him better. Like a lot of the stories in this collection, it’s deceptively simple and in only a few words explores the distances between us all, and the ways in which we try to bridge them.

Bleached Lichen Number Four is one of the most heart-wrenching stories of the collection, and depicts a man who attempts to communicate to his ex-girlfriend through the colour of her favourite paint. It, like many others in this fantastic collection, is a clever and poignant exploration of what it takes to be connected to another.

With More Sawn Off Tales, Gaffney has created very short stories that offer full, vivid and complete worlds for the reader to inhabit, and once inside they won’t want to leave.

The List May 2013

Thom Cuel AKA Theworkshy Fop

In 1919 Sherwood Anderson published Winesburg Ohio, a collection of 22 short stories. Each of the segments focused on an individual resident of the fictional town, isolating one character trait which had come to dominate their psyche, rendering them ‘grotesque’. The denizens of David Gaffney’s More Sawn-Off Tales are similarly marked – within these 150 word vignettes, we see snapshots of disconnected couples, unsatisfying jobs, the ideas which form in people’s heads without ever being ready to be released. This is a dark, urban world, for the most part, punctuated with flashes of understated surrealism and irony.

As you’d expect from Salt, what’s important in More Sawn-off Stories is often what’s left unsaid – Gaffney’s writing can be mysterious and wistful, and he avoids bringing his stories to conclusions – but there is a fierce and surprising imagination firing these brief pieces. The most successful make bold opening statements, before going on to occupy the same uneasy territory between surrealism and mundanity that Chris Morris explored in Jam. One story, for example, begins with the words ‘The frenetic gut-filth roar from DJ Stinger next door was seriously disturbing my alpacas’, immediately parachuting the reader into unfamiliar territory. Relationships become imbued with sinister qualities; in It Happens Inside, a radiologist breaks into a neighbour’s flat repeatedly in order to x-ray his belongings, getting to know him from the inside out. Everywhere’s West of Somewhereis more playful, providing a novel insight into trust issues: ‘Time slowed down as the vase arced through the air. You can discover everything about your girlfriend by tossing a breakable object towards her. Is she poised? Confident in her judgements? Does she seem willing to take responsibility for someone else’s actions?’ Elsewhere, the ironic tone gives way to bitterness: 'there is a place called Hope, and people live there. Hope is a town where you can rot away from the inside and no-one notices'

There is a lot of sex in these stories, but it is rarely erotic. It is either rigorously planned, as it is for Izzy, who was ‘willing to have sex with me only if it was in an empty property that we didn’t own – that was just the way she was, terrified of permanence’, or something to be engaged in for revenge, in the case of Hilary, who decides to seduce her mother’s ex-boyfriends one by one. Everyone over-analyses: ‘precise calibration was important to our relationship… we were continually striving to quantify the length of time we’d been a couple’. At times, reading More Sawn-Off Tales feels like viewing the emergence of a dystopia through the prism of a local newspaper's coverage. In Effective Calming Methods, the narrator opines 'I went home and set fire to the neighbours' shed... All I am waiting for is some intelligence to come out of the mouths of council staff'. Occasionally, things boil over completely into comic absurdity, as in The Listed Bridge, in which a man has become housebound because his penis has grown too large: ‘firemen would climb up on it and sit in a row swinging their legs’, whilst discussing the congestion problems caused by a low listed bridge in Kendal. This story exemplifies the way in which Gaffney combines the everyday with the bizarre.

More Sawn-Off Tales is rich with phrases which will stick in the reader’s memory (‘I keep a ball of tissue under my armpit and drop shreds of it into her food to keep her loyal’) and ideas which are ripe for expansion into longer stories, such as the psychiatrists who organise arts activities for their manic patients so that they can burgle their houses. Consumed in one sitting, some of the stories lose their impact under the weight of ideas, but Gaffney's world is an intriguing one to dip into - you just wouldn't want to live there.

Thom Cuel AKA The Workshy Fop

In 1919 Sherwood Anderson published Winesburg Ohio, a collection of 22 short stories. Each of the segments focused on an individual resident of the fictional town, isolating one character trait which had come to dominate their psyche, rendering them ‘grotesque’. The denizens of David Gaffney’s More Sawn-Off Tales are similarly marked – within these 150 word vignettes, we see snapshots of disconnected couples, unsatisfying jobs, the ideas which form in people’s heads without ever being ready to be released. This is a dark, urban world, for the most part, punctuated with flashes of understated surrealism and irony.

As you’d expect from Salt, what’s important in More Sawn-off Stories is often what’s left unsaid – Gaffney’s writing can be mysterious and wistful, and he avoids bringing his stories to conclusions – but there is a fierce and surprising imagination firing these brief pieces. The most successful make bold opening statements, before going on to occupy the same uneasy territory between surrealism and mundanity that Chris Morris explored in Jam. One story, for example, begins with the words ‘The frenetic gut-filth roar from DJ Stinger next door was seriously disturbing my alpacas’, immediately parachuting the reader into unfamiliar territory. Relationships become imbued with sinister qualities; in It Happens Inside, a radiologist breaks into a neighbour’s flat repeatedly in order to x-ray his belongings, getting to know him from the inside out. Everywhere’s West of Somewhereis more playful, providing a novel insight into trust issues: ‘Time slowed down as the vase arced through the air. You can discover everything about your girlfriend by tossing a breakable object towards her. Is she poised? Confident in her judgements? Does she seem willing to take responsibility for someone else’s actions?’ Elsewhere, the ironic tone gives way to bitterness: 'there is a place called Hope, and people live there. Hope is a town where you can rot away from the inside and no-one notices'

There is a lot of sex in these stories, but it is rarely erotic. It is either rigorously planned, as it is for Izzy, who was ‘willing to have sex with me only if it was in an empty property that we didn’t own – that was just the way she was, terrified of permanence’, or something to be engaged in for revenge, in the case of Hilary, who decides to seduce her mother’s ex-boyfriends one by one. Everyone over-analyses: ‘precise calibration was important to our relationship… we were continually striving to quantify the length of time we’d been a couple’. At times, reading More Sawn-Off Tales feels like viewing the emergence of a dystopia through the prism of a local newspaper's coverage. In Effective Calming Methods, the narrator opines 'I went home and set fire to the neighbours' shed... All I am waiting for is some intelligence to come out of the mouths of council staff'. Occasionally, things boil over completely into comic absurdity, as in The Listed Bridge, in which a man has become housebound because his penis has grown too large: ‘firemen would climb up on it and sit in a row swinging their legs’, whilst discussing the congestion problems caused by a low listed bridge in Kendal. This story exemplifies the way in which Gaffney combines the everyday with the bizarre.

More Sawn-Off Tales is rich with phrases which will stick in the reader’s memory (‘I keep a ball of tissue under my armpit and drop shreds of it into her food to keep her loyal’) and ideas which are ripe for expansion into longer stories, such as the psychiatrists who organise arts activities for their manic patients so that they can burgle their houses. Consumed in one sitting, some of the stories lose their impact under the weight of ideas, but Gaffney's world is an intriguing one to dip into - you just wouldn't want to live there.

Thom Cuel AKA The Workshy Fop

Structo Magazine

More Sawn-Off Tales is a collection of short stories, each exactly 150 words long. It’s a striking idea, and forms the follow-up to David Gaffney’s 2006 collection Sawn-Off Tales. The fact that a follow-up has been published at all should give you a clue to the quality of his writing.

In another life the Cumbrian author might have written his Sawn-Off Tales in verse, and their format is a fascinating aspect. Very short stories are hard to write well, and this is a master class, every piece a satisfying and (mostly) coherent whole. The stories manage to work structurally while at the same time being funny, or sad or disturbing—often all at once.

You might not believe yourself to be particularly interested in flash fiction (or microfiction or whatever it’s being called these days). You will be after this.

More Sawn-Off Tales was published in June by Salt Publishing.

Book Munch, June 2013

‘Almost every story flips your emotions and expectation when you turn from its opening page to its closing’ – More Sawn-Off Tales by David Gaffney

150 words is barely a long enough word count for Victoria Beckham’s daily shopping list. It is not enough space to create a story. Especially not a story that manages to be witty, surprising, eloquent, haunting, upsetting, or completely bizarre. And 150 words is surely not enough to create any stories that manage to be many of these things at once. Surely. But this is what David Gaffney has attempted, not once, but seventy-three times, in his latest collection. More Sawn-Off Tales is the follow up to the much vaunted Sawn-Off Tales of 2006. Any fans of that collection will not be disappointed.

Gaffney gets inside the mind of the characters that fill this collection, telling us more about them in the two pages they exist within than many authors tell us in a whole novel. In ‘It Happens Inside’ we encounter Sheila, a somewhat warped radiologist with a penchant for thievery: just five small paragraphs later we know all about the sad fantasy she lives in. We go from mistrusting her to feeling genuine sympathy in as much time as it takes to click your fingers. ‘In Oasis Leisure Lounge’ we route for Howard and his touching love for his overweight wife. In ‘Effective Calming Measures’ we find ourselves amused and horrified by the actions of a man who has serious grievances with the council. Those are just a few of the highlights. There’s no room here to go into detail about the man whose penis is so big he needs a physical theatre company to bring him to climax, or the oddball who dumps eyes in the bottom of a river, or even Valerie, the woman who appears to organise her dead boyfriends into a twisted version of a teddy bears’ picnic.

The plots of these stories sound surprising, and that’s because they are. In fact, the best thing about this collection is that almost every story flips your emotions and expectation when you turn from its opening page to its closing. So many of them bring a wry smile to the lips, or force out a loud chuckle that will make your fellow commuters stare at you like you’re as warped as the characters in the book you’re reading. And as much as you might begin to expect surprises as you progress through the collection, it’s almost impossible to second guess what direction the author will take us in.

Any Cop?: Whether we call it micro, flash, or short short fiction, there is no denying that pulling off stories of this length is a rare and enviable talent. Gaffney writes them with a skill I haven’t seen elsewhere. Much of the best flash fiction will pick an emotion and batter it, doing all it can to bring a tear to the eye or a laugh to the throat. Gaffney wouldn’t be satisfied with that. He wants it all at the same time. And often in this collection, he gets exactly that.

The Fiction Stroker

The trend of flash fiction has taken off in recent times. Manchester is fertile ground for flash-fiction writers with nights and groups spread all across the city. Indeed, David Gaffney will be a familiar name to many on the scene. 2006’s Sawn-Off Tales was his first collection of stories, and gave us tales exactly 150 words long. His latest collection More Sawn-Off Tales reprises this format collecting another 69 bizarre, kooky and downright weird snapshots of everyday life.

Reading these stories, it does feel like you are trapped inside Gaffney’s head. And it is a very strange place to inhabit if the stories contained within More Sawn-Off Tales are anything to go by. Serial killers, a man with a penis so large a theatre company has to turn him on and numerous shattered relationships all appear in this addictively bizarre collection.

There are some terrifyingly mundane descriptions of horror. The image of a farmer’s neglected sheep milling around with urban otters in a nightmarish future is one that will stay with you, as is the prospect of your eyes being scooped out with a melon baller. Tales of the Unexpected in its execution, it is a disturbing reflection of the characters inhabiting this collection.

The explorations of love are also diverse. From Graeme’s ranting of what constitutes love in ‘For the Lady’ through to Howard’s love for his overweight wife in ‘Oasis Leisure Lounge’, there is a surprisingly thorough examination of what makes relationships tick. Often life-changing decisions are made with the consequences rippling through your mind.

Gaffney’s narratives weave a taught line between the everyday and the fantastic. Here, the bizarre consequences of one story have an impact on the context of another deeper within the collection. This clever construction is a refreshing way of linking the stories together, and creates some amusing punchlines. Nowhere else will you find a man with “Nando’s breath” rubbing shoulders with a woman who wants to know her neighbour inside out by x-raying his possessions. It is his talent for weaving these strands together in a thoroughly ordinary but compelling way that makes this collection such a delight to read.

This is doubly surprising as all the worlds created come in at 150 words. It is barely time to write an introduction, never mind a story. Yet Gaffney’s creations are meticulously modelled. There are few conclusions to the stories, you’re left to draw your own opinions. Perhaps this is a collection that you’ll have to dip into rather than read in one-sitting, such is the lingering nature of many of the stories.

You’ll laugh, you’ll weep, and you’ll feel disgust and sorrow. It is a rare skill that can evoke such emotions, even rarer that someone can do it 69 times in one book. Thoroughly recommended.

The Fiction Stroker gives More Sawn-Off Tales five strokes out of five:

Cumberland News

"The stories constantly tease and surprise, each sentence convincing in itself, but the next one unsettling, disturbing our expectations, leaving us unsure where we are. They slip away from normality into the strangeness of other people"

More Sawn-off Tales by David Gaffney, by Steve Matthews

David Gaffney likes writing short stories, very short stories. Every one is 150 words long, no more, no less. In his terse, graphic paragraphs no word is wasted.

Each drama begins immediately. “She wore a dress with skulls on it”. “ ‘Here, catch,’ I said, and time slowed down as the vase arced through the air.” “I was a book recovery officer for the council.”

We know where we are and yet there is something quirky, a little odd, a little displaced to set the story going.

And then there is an uneasy sensual moment. The book recovery officer likes to “press my cheek against the leather and breathe in their damp earthiness”. Izzy “was terrified of permanence”. “She likes it that he doesn’t smell of Shake n’ Vac.”

The stories slip away from normality into the strangeness of other people.

Stories this short should work in stereotypes allowing our expectations to fill in for their brevity. But these stories don’t. They constantly tease and surprise, each sentence convincing in itself, but the next one unsettling, disturbing our expectations, leaving us unsure where we are.

Functional Market Area begins: “I helped Ivan load the eyes into his van.” The lazy pun is unsettling. We learn that “He loved driving the eyes”, that “He kept a glass eye himself from a woman he was in love with, and he said it had a pleasant aroma like the underside of a wristwatch that hadn’t been taken off for years.” Perhaps Ivan had no customers and tossed the eyes “into some deep river and there they lay – teddybears’ eyes, dolls’ eyes, human eyes, staring at the fish.”

You see how they work and they are here in all their profusion. Over seventy stories, everyone different in its own unpredictable way.

Take some titles: Blood in Flight; The Building with the Hole; The Mousemats Say Innovate or Die; The Three Rooms in Valerie’s Head and The Periphery is Everywhere.

Valerie’s Head is a moral fable. She recalled her past boyfriends from the cellar and was able to control them. “The trouble was having no space in the front room for anything else.”

These are all contemporary tales, tales of urban life, of loneliness and meetings and failing relationships, of brown-field sites and blocks of flats. His people are like Phoebe, who couldn’t sleep because the cooling fan in her lap top has broken or like the man who left his wife “and moved into a converted barrel organ factory opposite a building with giant question mark on its side.” Or Sheila who “was a radiologist and liked to steal things from her neighbour’s flat and X-ray them at work”. Or Boylan who “was a smell comedian at the deaf and blind club”.

And then there are the phrases and the adjectives: “His nostrils prickled with the carbonised atoms of nothingness”; “it smelt like old wallpaper”; “flattened and sucked dry like extinct grass”; “her skin was the colour of polished rice” and “where the sky is the colour of aged Tupperware”.

I’ve never read anything like these stories before. They are idiosyncratic, imaginative, inventive. David Gaffney lives in Manchester, but comes from Cleator Moor. These really are sawn-off tales.

Cumberland News, August 2013

" These are the most wonderful and clever flash fiction short stories. I thought telling a story in 300 words or less was impossible. It isn't, as David Gaffney proves."

Fennel Books.